Duration of service in the tsarist army. Military service

This newsletter is an answer to the reader’s question: Where can you find out when specific people born in the second half of the 19th century served in the army, if their place of residence, year of birth, and peasants are known? The answer turned out to be somewhat extended, I will tell you in general about the military service of the unprivileged classes, but the one who asked it will someday go back centuries, so it will be useful to him.

But I really like the way the question is posed. The fact is that a person is interested not only in the dates and places of birth of his ancestors, not only in archival information that can be neatly filed and put in a closet, but also in their entire lives. How cool it is, for example, to trace the progress of your ancestor’s military service, to find out not only what campaigns he went on, but also how he lived, what he ate, how he spent his time, and even find his fellow soldiers. I am delighted, but this is a very labor-intensive task.

Where to look.

Information on this matter can be sought from two sides. You can start locally permanent residence, find out how the ancestor got into the army, where he could have been sent, and then search through military documents, which have been preserved in abundance. All punishments, rewards, transfers - everything was reflected there, these are huge volumes, some inventories are so voluminous that you cannot read them in one visit to the archive. And you can start searching through documents that arise when a soldier returns home after serving. At the same time, they often wrote which regiment he was a retired soldier, and then again you have to search through military documents. Officers had service records, but privates, as a rule, did not.

Look at the website Archives of Russia (www.rusarchives.ru) Russian military-historical archive, regional archives, even in the archive of film and photo documents you can find your ancestors. In the regional archives you can look for draft lists - documents of military registration of the population. They were compiled on the basis of metric books in 2 copies: one for the volost government or district presence for military service, the other for the consistory. Contained information: last name, first name, patronymic, age, place of residence, marital status, information about relatives, education and health status. They are stored in the funds of provincial and district conscription offices, spiritual consistories, city dumas, city councils, volost boards . I won’t go into specifics; the coordinates, and often the archive sites, are available online. For example, in the State Archives of the Republic of Mari-El, information on the military department is contained in the documents of district military presences (1856-1918), district military commanders (1874-1917).

Last time I promised not to give links, but since I already gave one, I’ll give you another one, with pictures. gorod.crimea.edu/librari/rusmundirend/index.html - the uniforms your ancestors wore are depicted there, something to imagine in real life.

Recruit era

By decree of Peter I of November 17, 1699, the creation of a regular Russian Army began. The army was recruited with soldiers on a mixed basis. “Volnitsa” is the admission into the army of free people personally. "Datochnye" - the forced assignment of serfs belonging to landowners and monasteries to the army. It was established - 2 recruits for every 500 "dacha" people. It was possible to replace one recruit with a cash contribution of 11 rubles. Soldiers were accepted between the ages of 15 and 35. However, the first recruitment showed that the “freemen” were clearly not enough, and the landowners preferred to pay money instead of supplying recruits.

Since 1703, a single principle for staffing the army with soldiers was introduced - conscription. Recruitment was announced irregularly by decrees of the tsar, depending on the needs of the army.

Initially, recruits were trained directly in the regiments, but from 1706 training was introduced at recruiting stations. In this regard, it is impossible to find out which regiment your ancestor was drafted into immediately at the place of conscription, but this can be found out if you dig further. The length of military service was not determined (for life). Those subject to conscription could nominate a replacement for themselves. Only those completely unfit for service were fired.

The soldiers are not monks, no one demanded complete abstinence from them, and with special permission they could marry, and their sons were immediately enrolled in the army upon birth. military service. At six months, when their mothers stopped breastfeeding them, they were enrolled in allowances, and a little later they were sent to garrison schools, but this was after 1721. Peter the Great then founded a garrison school for each regiment for 50 soldiers’ sons. The schools taught literacy, writing, crafts, music and singing. From among them, the units received barbers, doctors, musicians, clerks, shoemakers, saddlers, tailors, blacksmiths, forges and other specialists.

The army was staffed with non-commissioned officers by promoting the most capable and efficient soldiers to non-commissioned officer ranks. Later, many non-commissioned officers attended cantonist schools.

In 1766, a document was published that streamlined the army recruitment system: “General Institution on the collection of recruits in the state and on the procedures that should be followed during recruitment.” Recruitment, in addition to serfs and state peasants, was extended to merchants, courtyard people, yasak, black sowing, clergy, foreigners, and persons assigned to state-owned factories. Only artisans and merchants were allowed to make a cash contribution instead of a recruit. The age of the recruits was set from 17 to 35 years old, height not lower than 159 cm.

Until the 1780s, the main burden of recruitment was borne by the central regions of Russia, as well as the ethnically mixed population of the Volga region (Russians, Mordvins, Chuvash, Bashkirs, Tatars, etc.). In Ukraine, which was still being populated at that time, there were various shapes formations recruited locally (Cossacks). The first steps to create tax and administrative uniformity were taken under Catherine II and accelerated under Paul I: in the territories ceded to Russia after the first partition of Poland, a poll tax was immediately introduced - instead of the previous Polish "smoke" tax - and recruitment began kit. At the same time, the poll tax and conscription were extended to Hetman Ukraine and the so-called Novorossiya and southern Russian regions. Finally, in 1796 it was the turn of the Baltic provinces. Along with considerations of administrative and tax uniformity, as well as in view of the growing need for soldiers, decrees constantly emphasized the need for an equal distribution of the burden of recruitment among everyone and the liberation of the central Russian provinces from it. In 1803, 40% of the recruits came from ethnically Russian, 14% from Lithuanian-Belarusian and about 17% from Ukrainian (in today's sense) lands. Almost 30% were non-East Slavic peoples: the Balts, Finns, peoples of the Volga region, Tatars.

In 1805, garrison schools for soldiers' children were reorganized and received the name cantonist. The name was borrowed from Prussia (from regimental districts, cantons). Under Nicholas I, cantonist institutions provided the army with combat non-commissioned officers, musicians, topographers, conductors, draftsmen, auditors, clerks and all kinds of artisans.

In the first half of the 19th century, the army recruitment system did not undergo significant changes. In 1802, the 73rd recruitment was carried out at the rate of two recruits from 500 people. Depending on the needs of the army, recruitment could not be carried out at all, but there could be two recruitments per year. For example, in 1804 the recruitment was one person per 500, and in 1806, five people per 500.

In the face of the danger of a large-scale war with Napoleon, the government resorted to a previously unused method of forced recruitment (now called mobilization). On November 30, 1806, with the manifesto “On the Formation of the Militia,” landowners were obliged to field the maximum possible number of their serfs capable of bearing arms. These people remained in the possession of the landowners and after the dissolution of the police in 1807, the warriors returned to the landowners. More than 612 thousand people were recruited into the police. This was the first successful experience of mobilization in Russia.

Since 1806, reserve recruiting depots have been created in which recruits were trained. They were sent to the regiments as the regiments needed replenishment. Thus, it was possible to ensure the constant combat effectiveness of the regiments. Previously, after battles and losses suffered, the regiment dropped out of the active army for a long time (until it received and trained new recruits).

Planned recruitments were carried out in November of each year.

1812 required three recruitments, with the total number of recruits being 20 from 500.

In July 1812, the government carried out the second mobilization in this century - the manifesto “On the collection of the zemstvo militia.” The number of militia warriors was about 300 thousand people. The warriors were commanded either by the landowners themselves or by retired officers. A number of large aristocrats formed several regiments from their serfs at their own expense and transferred them to the army. Some of these regiments were later assigned to the army. The most famous are the cavalry squadron of V.P. Skarzhinsky, the Cossack regiment of Count M.A. Dmitriev-Mamonov, the hussar regiment of Count P.I. Saltykov (later the Irkutsk Hussar Regiment), battalion Grand Duchess Ekaterina Pavlovna.

In addition, there were special units that in the first half of the 19th century were not included in the army, but participated in all the wars waged by Russia. These were Cossacks - Cossack units. The Cossacks were not serfs or state peasants. They were free people, but in exchange for their freedom they supplied the country with a certain number of ready-made, armed cavalry units. The Cossack lands themselves determined the order and methods of recruiting soldiers and officers. They armed and trained these units at their own expense. IN Peaceful time the Cossacks carried border service in their places of residence. They closed the border very efficiently.

After the end of the war and the foreign campaign, recruitment was carried out only in 1818. There was no recruitment in 1821-23. During this period, up to several thousand people were recruited into the army by capturing vagabonds, runaway serfs, and criminals.

A military settlement is a special organization of troops (1810-1857) with the aim of reducing military expenses. The point was to raise a kind of militarized peasantry that would combine farming with military service. The state bought land and peasants from bankrupt landowners, introduced military units there, and all residents were transferred to martial law. Military units settled on state-owned lands, which local residents, turned into soldiers, combined military service with farming. The children of all residents turned into cantonists. Strict regulation, drill, and strict regime caused uprisings that were suppressed extremely harshly. It was in every way repressive system, especially in the west and north-west of the country; in 1826 it enslaved 374 thousand people (of which 156 thousand were active and “working” soldiers).

In 1816-1826, about 1/4 of the army was in the position of military settlers. After the revolt of the Novgorod settlements in 1831, the system was modified. By 1850 the number of villagers-owners exceeded 700 thousand people.

In 1824, all cantonists were subordinated to the department of military settlements. They were to be trained for service as lower ranks - from drummers and paramedics to non-commissioned officers.

Since 1827, Jews began to be recruited into the army as soldiers. Before this, military service was replaced for them by a cash tax. For Jews, the conscription quota was 10 recruits per thousand men annually. Jewish communities were also required to allocate a “penalty” number of recruits for tax arrears and escape of conscripts. Unlike other population groups, which supplied recruits aged 20-35, the age for Jewish recruits was set from 12 to 25 years. Adults were immediately assigned to active service, and minors, from 12 to 18 years old, were sent to battalions and schools “to prepare for military service.” The reason and pretext for this measure were, firstly, early age marriage of Jews and, secondly, the hope of the Russian side that during military service it would be possible to convert Jews to Christianity. This was often possible - sometimes through the use of torture; in addition, 25 rubles were given as a reward for converting to Christianity. In many battalions they quickly baptized everyone and at the same time gave the names of their recipients, which led to the cessation of correspondence with relatives, because the addressee Jewish surname"dropped out." As I wrote in the section about registry books, the registry books of the military department have been preserved very poorly, so there is practically no possibility of finding baptized Jewish recruits.

Children were hidden, Jewish families fled to the provinces of the Kingdom of Poland or Bessarabia, to which the law on cantonists did not apply. Often, Jewish public administrations (kagals) handed over orphans, children of widows, boys 7-8 years old, who, according to a false oath, 12 witnesses recorded as 12 years old, replaced their children with volunteers or Jews from other communities. Often the children of the poor were taken instead of the children of the rich. Jewish recruits were sent to canton schools with the most severe regime, and to places as far as possible from the “Pale of Settlement” (Urals, Siberia, Volga region). It was forbidden to speak native language. Years spent in cantonist schools did not count toward the period of military service, which was 25 years for recruits.

Similar methods - conscription of children and more or less forced baptism - under Peter I were used in relation to the Volga Tatars. Since then, in the Tatar regions, in favor of baptism, they acted mainly through exemption from taxes and conscription, sometimes, however, shifting this burden from newly converted Christians to their stubborn fellow countrymen - Muslims and pagans. In relation to the Jews, the decree of 1827 first formulated a goal: through conscription and other measures, mainly in the field of education, to achieve their civil and religious alignment with others - it seems that the goal sounds good, but what an atrocity it turned out to be.

In the same year, 1827, the cantonist schools were transformed into half-companies, companies and battalions of cantonists. In them, cantonists studied literacy and military affairs, and upon reaching conscription age they were sent to the army as musicians, shoemakers, paramedics, tailors, clerks, gunsmiths, barbers, and treasurers. A significant part of the cantonists were sent to training carabinieri regiments and, after graduation, became excellent non-commissioned officers. The authority of the schools of military cantonists became so high that the children of poor nobles and chief officers often enrolled in them.

After 1827, the bulk of non-commissioned officers were recruited from training carabinieri regiments, i.e. The quality of non-commissioned officers steadily increased. Things got to the point that the best of the non-commissioned officers were sent to officer schools, the Noble Regiment, and cadet corps as teachers of combat and physical training, and shooting.

Since 1831, conscription was extended to the children of priests who did not follow the spiritual line (that is, who did not study in theological seminaries).

From the point of view of the communities, conscription was something like a human sacrifice. Therefore, they tried to send into the army, first of all, men who were considered “worthless”, were ballast for the community, or deserved punishment. To prevent them from going on the run, they were marked and sometimes locked up. For the recruits, their position was tantamount to “civil death.” They never returned home. Their class affiliation changed - from townspeople or peasants they became soldiers. Most of troops stood in the national outskirts and often moved, the troops functioned as an armed force, which was used for the defense of the country and conquests, and within the empire as a police force and had no ties with the population. Even the marriage of soldiers took place in a strange way For example, it is not uncommon for a soldier to marry the widow of a deceased comrade, because she already had a place to live and was accustomed to a soldier’s life, about which a corresponding order was issued. And the children became cantonists.

The new Recruitment Charter significantly streamlined the recruiting system. According to this charter, all taxable estates (categories of the population obliged to pay taxes) were rewritten and divided into thousandth plots (the territory where a thousand people of the taxable estate live). Recruits were now taken in an orderly manner from the sites. Some wealthy classes were exempt from fielding a recruit, but paid a thousand rubles instead of a recruit. A number of regions of the country were exempted from conscription duties. For example, the region of the Cossack troops, the Arkhangelsk province, a strip of one hundred miles along the borders with Austria and Prussia. The recruitment deadlines were determined from November 1 to December 31. The requirements for height (2 arshins 3 inches), age (from 20 to 35 years), and health status were particularly specified.

In 1833, instead of general recruitment, private ones began to be practiced, i.e. recruitment of recruits is not uniformly from the entire territory, but from individual provinces.

In 1834, a system of indefinite leave for soldiers was introduced. After 20 years of service, a soldier could be discharged on indefinite leave, but if necessary (usually in the event of war) could be recruited into the army again.

In 1851, the period of compulsory service for soldiers was established at 15 years.

In 1854, the recruitment was divided into three types: ordinary (age 22-35, height not less than 2 arshins 4 inches), reinforced (age not determined, height not less than 2 arshins 3.5 inches), extraordinary (height not less than 2 arshins 3 top).

By 1856, there were about 380 thousand cantonists in the country. This year, Alexander II destroyed this system with his coronation manifesto. Children of soldiers were freed from a previously obligatory military future. All Jewish soldiers and cantonists under 20 years of age could return to their families. At the end of their service, Jewish soldiers and their descendants received the right to settle outside the Pale of Settlement. Most often, they remained to live where the end of their service found them. Jewish communities began to emerge here, especially since in the middle of the 19th century other categories of Jews also received the right to settle in the inner provinces of Russia. The standard of living in them was higher than in the Pale of Settlement; there were more opportunities to find work, and the local population was tolerant of Jews.

Retired cantonists lived mainly in cities (in Moscow in the 50s of the 19th century there were about 500 of them), but they were also engaged in agriculture. Former cantonists received a pension of 40 rubles, which allowed their families to exist and their many children to receive a secular education.

In 1859, it was allowed to release soldiers on indefinite leave (what is now called “discharge to the reserve”) after 12 years of service.

Since 1863, the age of recruits was limited to 30 years.

Since 1871, a system of long-term servicemen was introduced. Those. A non-commissioned officer, after completing a mandatory service period of 15 years, could remain to serve beyond this period, for which he received a number of benefits and increased pay.

So, let's summarize.

Recruitment - a method of recruiting an army in 1699-1874. Recruits were supplied by tax-paying classes. At first, recruitments were random, as needed. They became annual in 1831, with the publication of the recruiting regulations. Russia was divided into 2 zones, eastern and western, and recruits were taken annually from each in turn, 2 years were counted as 1 recruitment. Usually they took 5 people from 1 thousand. With increased recruitment, this figure changed and reached 70 during the Sevastopol defense. The age of the recruits ranged from 17 to 32 years; The service life until 1793 was lifelong, in 1793-1834 - 25 years, in 1834-1855 - 20 years (and 5 years "on vacation" - in reserve), in 1855-1872 it was reduced to 12, 10 and 7 years (respectively " on vacation" for another 3, 5 and 8 years). The rule for supplying soldiers changed many times, for example, until 1724 one recruit was required to be supplied from 20 households: then from every thousand souls - 5-7 (if necessary, up to 10) recruits.

In 1874, the conscription obligation, which had existed for almost two centuries, was abolished. A new method of recruiting an army is being introduced - universal conscription. The word "recruit" was replaced with the word "rookie".

The era of universal conscription

The reform program proposed by the nationalist-minded Minister of War D.A. Milyutin (1861-1881) was based on the fact that it was necessary to use the “natural superiority” of the Russian element, that is, that non-Russians in the army, if not Russified, were then exposed to Russian influence due to their location and dislocations. According to him, the renewed army should become a crucible for the melting of nations, in which the Russian majority will easily rise to the top. Each military unit must contain at least 75% “Russians” (that is, Great Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians). An exception to the rule about universal military duty there was Finland - since 1878 it had new military legislation - further, the territory of the Cossack troops, the Caucasian provinces, Turkestan, as well as nomadic peoples Northern Siberia and the so-called steppe, which largely coincides with the territory of Kazakhstan.

All young men who turned 20 by January 1 were drafted into the army. The conscription began in November of each year. Priests and doctors were exempted from military service and a deferment of up to 28 years was given to persons undergoing training in educational institutions. The number of those subject to conscription far exceeded the needs of the army, and therefore everyone who was not exempt from service drew lots. Those who were drawn by lot (about one in five) went to serve. The rest were enlisted in the militia and were subject to conscription war time or if necessary. They were in the militia until they were 40 years old.

The period of military service was set at 6 years plus 9 years in reserve (they could be called up if necessary or in wartime). In Turkestan, Transbaikalia and the Far East, as in the navy, the service life was 7 years, plus three years in reserve. By 1881, the period of active military service was reduced to 5 years. Presentation of a certificate of passing final exams served as a basis for reducing service life. Volunteers could join the regiment from the age of 17.

The Law on Universal Conscription (1874) provided for the equality of Jews with other conscripts and volunteers, but restrictions soon followed that crossed out this provision.

Big noise outside Russian Empire caused by the abolition of Finland's autonomy (1899) and the liquidation of its own military organization (1901). Back in 1871, Minister of War Milyutin, by reforming Finnish legislation, sought to abolish its independence, but at that time his proposals were not successful. Thirty years later followed the introduction of conscription in Finland. Russian model And Russian example. It unexpectedly met resistance in this country, where national unity had already taken shape over the past years. In 1903, only two-thirds of recruits showed up for medical examination at recruiting stations. Autonomy and its own armed forces have already become so national symbol that St. Petersburg, under the pressure of the revolutionary events of 1905-1906, again provided Finland with its own constitution, being satisfied with Finland’s financial investments in defense. Since then, Finland has not been required to perform military service.

At the beginning of the 20th century, of all the subjects of the Russian Empire who had reached conscription age (20 years), about 1/3 were called up for active military service by lot. The rest were enlisted in the militia, they underwent training at the training camp. Call once a year - from September 15 or October 1 to November 1 or 15 - depending on the timing of the harvest. Duration of service (since 1906) in the ground forces: 3 years in infantry and artillery (except cavalry); 4 years in other branches of the military. After this, they were enlisted in the reserves, which were called up only in case of war. The reserve period is 13-15 years. In the navy, conscript service is 5 years and 5 years in reserve.

The following were not subject to conscription for military service: residents of remote places (Kamchatka, Sakhalin, some areas of the Yakut region, Yenisei province, Tomsk, Tobolsk provinces, as well as Finland), foreigners of Siberia (except for Koreans and Bukhtarminians), Astrakhan, Arkhangelsk provinces, Steppe Territory, Transcaspian region and the population of Turkestan. Some foreigners of the Caucasus region and Stavropol province (Kurds, Abkhazians, Kalmyks, Nogais, etc.) paid a cash tax instead of military service. Finland contributed 12 million marks from the treasury annually. Persons of Jewish nationality were not allowed into the fleet.

There were benefits for marital status. Not subject to conscription: the only son in the family; the only son capable of working with an incapacitated father or widowed mother; the only brother for orphans under 16 years of age; the only grandson with an incapacitated grandmother and grandfather without adult sons, an illegitimate son with his mother (in his care), a lonely widower with children. Subject to conscription in the event of a shortage of suitable conscripts: the only son capable of working, with an elderly father (50 years old), next to a brother who died or disappeared in the service, next to a brother still serving in the army.

Based on their professional affiliation, the following were exempted from military service: Christian, Muslim clergy (muezzins at least 22 years old), scientists (academicians, adjuncts, professors, dissectors with assistants, lecturers of oriental languages, associate professors and private assistant professors), artists of the Academy of Arts sent abroad for improvement, some officials in the scientific and educational department.

Received a deferment from conscription: up to 30 years of age, government scholarship recipients preparing to take up scientific and educational positions, after which they are completely released; up to 28 years of age, students of higher educational institutions with a 5-year course; up to 27 years of age in higher education institutions with a 4-year course; up to 24 years of age, students of secondary educational institutions; students of all schools, upon request and agreement of ministers; for 5 years - candidates for preaching of Evangelical Lutherans. In wartime, persons with a deferment were taken into service until the completion of the course by the Highest permission.

Sometimes the terms of active service were shortened. Persons with higher, secondary (1st category) and lower (II category) education served in the military for 3 years, and for 2 years - persons who passed the exam to become a reserve warrant officer. Doctors and pharmacists served in the ranks for 4 months, and then served in their specialty for 1 year 8 months. In the navy, persons with an 11th grade education (lower educational institutions) served for 2 years and were in the reserve for 7 years. Teachers and officials in the academic and educational department served for 2 years, and in the temporary 5-year position from December 1, 1912 - 1 year. Paramedics who graduated from special naval and military schools served for 1.5 years. Graduates of the schools for soldiers' children of the Guard troops served for 5 years, starting from the age of 18-20. Technicians and pyrotechnicians of the artillery department served for 4 years after graduation. Civilian sailors were given a deferment until the end of the contract (no more than a year).

The entire male population capable of bearing arms and not enlisted in the troops (in active service and in reserve) up to 43 years of age, and officers up to 50-55 years of age, constituted a compulsory state militia “to assist standing troops in case of war.” They were called: militia warriors and militia officers. Warriors were divided into 2 categories: 1st category for service in the field army, 2nd category for service in the rear.

Military conscription of the Cossacks is a special issue. All men were required to serve without ransom or replacement on their own horses with their own equipment. The entire army provided servicemen and militia. Servicemen were divided into 3 categories: 1 preparatory (20-21 years old) underwent military training. II combatant (21-33 years old) served directly. III reserve (33-38 years old) deployed troops for the war and replenished losses. During the war, everyone served without regard to rank. Militia - all those capable of service, but not included in the service, formed special units.

Cossacks had benefits: according to marital status (1 employee in the family, 2 or more family members are already serving); by property (fire victims who became impoverished for no reason of their own); by education (depending on education, they served from 1 to 3 years in the ranks).

General mobilization

In August-December 1914, general mobilization took place. 5,115,000 people were drafted into the army. In 1915, six sets of recruits and senior militia were made. The same thing happened in 1916. In 1917 they managed to conduct two sets of recruits.

The manifesto on conscription into labor detachments dated June 25, 1916, addressed to the Steppe, Turkestan and the Caucasus, met with massive resistance in the first of the two named regions. After the brutal suppression of the uprising by Russian troops from neighboring Siberia, they managed to take about 50% of the planned contingent of recruits by the end of autumn 1916.

National activists from the Azerbaijani-Turkic influential strata did not want to be content with participating in “inferior” labor groups, as provided for in the Manifesto. The petition they submitted received a positive response. From Azerbaijani-Turks and Muslim highlanders North Caucasus The "Wild Division" was formed.

Already in 1915, Georgians and Armenians received the right to create volunteer formations within the Caucasian Front.

Crimean Tatar units were sent to Western Front. Troops with a large number of Poles fought as far as possible from Polish lands. After divided Poland ceased to exist in 1916, the formation of Polish formations was allowed, which led to the creation of several Polish corps in 1917. The Poles had a relatively high desertion rate since the beginning of the war.

In 1915, after Russia lost Courland, Latvians were allowed to organize national formations. As is known, along with sailors, the most important support of Bolshevism in early period battalions of Latvian riflemen became his power.

The Estonians only received permission from the Provisional Government in 1917 and with serious reservations to create their own formations.

Representatives of the Ukrainian nation were concentrated on the Romanian and Southwestern fronts. They made up about a third of the entire rank and file here. At the same time, they were scattered along all fronts and garrisons. Therefore, until 1917, it was difficult for the Central Rada in Kyiv to create national military units.

We won’t talk about the Red Army, but how to search for documents about Soviet-era military personnel was discussed in the mailing list to departmental archives, which contained Boginsky’s advice.

In our special issue “Professional” (“Red Star” No. 228) we talked about the fact that the regular Russian army not only began its formation in Peter’s times on a contract basis, but also then, in all subsequent reigns - from Catherine I to Nicholas II - partly consisted of “lower ranks” who voluntarily entered the service, that is, soldiers and non-commissioned officers. The system of recruiting the armed forces was changing: there was conscription, there was all-class conscription, but “contract soldiers”, speaking modern language, they still remained in the army... Today we will continue the story on the same topic and try to understand what benefit these same “contract soldiers” of non-noble rank brought to the army and why they themselves voluntarily served in its ranks.

About the soldiers who were old enough to be grandfathers to officers

So-called“recruitment” existed from 1699 (by the way, the word “recruit” itself was introduced into use only in 1705) and before, in accordance with the manifesto of Alexander II, Russia switched to “all-class military service” in 1874.

It is known that people were recruited from the age of 20, and not from the age of 18, as we were called up in the 20th century, which, you see, represents a certain difference. Then the same age - 20 years - remained during the transition to conscription service... It would also not be superfluous to say that people under the age of 35 were taken as recruits, which means that with a twenty-five-year service life a soldier could, as it was said then , “pull the strap” until a very respectable age - until the seventh decade. However, in the “era of the Napoleonic Wars” they even began to hire 40-year-olds... As a result, the army, or rather its soldier composition, grew old inexorably and inevitably.

But the officer corps was not only young, but rather, simply young. Let's take Dmitry Tselorungo's book “Officers of the Russian Army - Participants in the Battle of Borodino” and open a table that shows the age level of these officers. It analyzed data for 2,074 people, and from this figure calculations were made that were quite consistent with the “arithmetic average” for the entire Russian army of 1812.

The main age of the officers who fought at Borodino was from 21 to 25 years old - 782 people, or 37.7 percent. 421 people, or 20.3 percent of all officers, were between 26 and 30 years old. Overall, officers aged 21 to 30 accounted for almost 60 percent of the total. Moreover, it should be added that 276 people - 13.3 percent - were aged 19-20 years; 88 people – 4.2 percent – are 17-18 years old; 18 people - 0.9 percent - were 15-16 years old, and another 0.05 percent was a single young officer 14 years old. By the way, under Borodin there was also only one officer over the age of 55... In general, almost 80 percent of the commanders in the army were between the ages of 14 and 30, and just over twenty of those who were over 30. They were led - let us remember the famous lines of poetry - by “young generals of yesteryear”: Count Miloradovich, who commanded the troops of the right flank at Borodin, was 40, brigade commander Tuchkov 4th was 35, and chief of artillery of the 1st Army, Count Kutaisov, was 28...

So imagine a completely ordinary picture: a 17-year-old warrant officer, a young man at the age of our modern Suvorov senior student, goes out in front of the formation of his platoon. Standing in front of him are men of 40 to 50 years old. The officer greets them with the exclamation “Hello, guys!”, and the gray-haired “guys” unanimously shout back, “We wish you good health, your honor!” “Come on, come here! - the ensign calls some 60-year-old grandfather out of formation. “Explain to me, brother...”

All this was as it should be: the form of greeting - “guys”, and the liberal-condescending address to the soldier “brother”, and the conversation with the lower rank, a representative of the “vile class”, exclusively on a personal basis. The latter, however, has come down to our times - some bosses see any of their subordinates as a “lower rank”...

By the way, the memory of those morals was preserved both in old soldiers’ songs - “Soldiers, brave boys!”, and in literature - “Guys, isn’t Moscow behind us?”

Of course, much can be explained by the peculiarities of serfdom, that distant time when a soldier saw in an officer, first of all, a representative of the upper class, to whom he was always obliged to obey unquestioningly. But still, was it so easy for yesterday’s graduates of cadet corps, recent cadets who learned the basics of practical military science here in the regiment under the leadership of “uncles” - experienced soldiers, to command elderly soldiers who sometimes “broke” more than one campaign?

Here, by the way, although the time is somewhat different - already the most late XIX century, - but a very accurate description of a similar situation, taken from the book of Count Alexei Alekseevich Ignatiev “Fifty Years in Service”:

“I come to class...

“Command,” I say to the non-commissioned officer.

He clearly pronounces the command, upon which my students quickly scatter around the hall in a checkerboard pattern.

- Protect your right cheek, stab to the left, cut down to the right!

The whistle of checkers in the air, and again - complete silence.

What should I teach here? God willing, I wish I could remember all this myself for the review, where I will have to command.

“It’s not very clean,” the sergeant tells me intelligibly, “they do it very badly there in the third platoon.”

I’m silent because the soldiers do everything better than I do.”

Meanwhile, Count Ignatiev was not one of the “regimental cadets”, but was educated in the Corps of Pages, one of the best military educational institutions in Russia...

It is clear that between the two categories of military personnel - officers and soldiers - there had to be some kind of, let's say, connecting link. One can also guess that sergeants - non-commissioned officers at that time - should have been such.

Yes, theoretically this is true. But we have a sad experience Soviet army, where sergeants were often called “private soldiers with stripes” and complained all the time that officers had to replace them... Moreover, if representatives of a socially united society served in the Soviet Army, then in the Russian Army, as already said, officers represented one class, soldiers - another. And although today the “class approach” is not in fashion, however, honestly, we should not forget about “class contradictions” and, by the way, about “class hatred”. It is clear that in the depths of his soul the peasant did not particularly favor the landowner-nobleman - and, I think, even at a time when one of them wore shoulder straps, and the other wore epaulettes. The exception, of course, is the year 1812, when the fate of the Fatherland was decided. It is known that this time became an era of unprecedented unity of all layers of Russian society, and those who found themselves at the theater of war - soldiers, officers and generals - then equally shared the march loads, stale crackers and enemy bullets... But, fortunately or unfortunately, this did not happen too often in our history.

But in peacetime, as well as during some local military campaigns, there was no trace of such closeness in the army. So is it worth clarifying that not every non-commissioned officer sought to curry favor with the officers, in one sense or another to “betray” his comrades. In the name of what? There was, of course, a material interest: if during the reign of Emperor Paul I in the Life Guards Hussar Regiment, a combat hussar received 22 rubles a year, then a non-commissioned officer received 60, almost three times more. But in our lives, human relationships are not always determined by money. Therefore, a normal, let’s say, non-commissioned officer more often found himself on the soldier’s side, trying in every possible way to cover up his sins and protect him from the command... It was, of course, different, as Count Ignatiev again testifies: “Latvians are the most serviceable soldiers , - bad riders, but people with a strong will, turned into fierce enemies of the soldiers as soon as they received non-commissioned officer braid.”

However, the role of that very connecting link, and maybe even some kind of “layer”, was, of course, not they, but, again, “contract soldiers” - that is, the lower ranks who served under the contract...

“Where should the soldier go now?”

Before 1793 Russian soldier served for life. Then - twenty-five years. It is known that Emperor Alexander Pavlovich, at the end of his stormy and controversial quarter-century reign, wearily complained to those close to him: “Even a soldier, after twenty-five years of service, is being released to retire...” This period remained in the memory of posterity, in which it seemed to “extend” to everything XIX century.

And here is what Colonel Pavel Ivanovich Pestel, the head of the secret Southern Society, wrote: “The term for service, determined at 25 years, is so long by any measure that few soldiers go through it and stand it, and therefore, from infancy, they get used to looking at military service as a severe misfortune and almost as a decisive sentence to death "

What is said about the “sentence to death” is quite fair. Without even touching on participation in hostilities, let us clarify that, firstly, life expectancy in Russia in the century before last was still shorter than now, and, as we said, they could be recruited even at a fair age. Secondly, the army service of that time had its own specifics. “Kill nine, train the tenth!” - used to say Grand Duke and Tsarevich Konstantin Pavlovich, a veteran of the Italian and Swiss campaigns. He, who on April 19, 1799 personally led a company in an attack near Basignano, distinguished himself at Tidone, Trebbia and Novi, showed considerable courage in the Alpine Mountains, for which he was awarded by his father Emperor Paul I the diamond insignia of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, “became famous” later for such “pearls” as “war spoils the army” and “these people don’t know how to do anything except fight!”

« Recruit

- a recruit, a newcomer to military service, who has entered the ranks of soldiers, privates, by conscription or for hire.”

(Explanatory dictionary of the living Great Russian language.)

Although this should not be surprising: after all, in the army, especially in the regiments of the guard, the imperial family first of all saw the support and protection of the throne from all sorts of enemies, and Russian history proved quite convincingly that the external danger for our sovereigns was much less dangerous than the internal one. Whatever you say, not one of them was killed by the interventionists... That is why the soldiers were trained for years, so that at any moment, without hesitation, they would be ready to fulfill the highest will.

It is clear that in a quarter of a century almost any man could be turned into a capable soldier. Moreover, they took into the army, and even more so into the guard, not just anyone, but in accordance with certain rules.

The recruit who came to the service was taught not only the basics of military art, but also the rules of behavior, one might even say, “noble manners.” Thus, in the “Instructions for the Colonel’s Cavalry Regiment” of 1766 it is said, “so that the peasant’s mean habit, evasion, grimace, scratching during conversation would be completely exterminated from him”. The aforementioned Tsarevich Konstantin demanded “so that people would disdain to sound like peasants, ... so that every person would be able to speak decently, intelligently and without shouting, would answer his superior without being timid or insolent in front of him, would always have the appearance of a soldier with proper posture, for knowing his business, He has nothing to fear..."

Quite soon - under the influence of persuasion and everyday drill, as well as, if necessary, a fist and a rod - the recruit turned into a completely different person. And not only externally: he was already becoming different in essence, because the soldier was emerging from serfdom, and long years services completely separated him from his family, homeland, and usual way of life. That’s why, after serving, the veteran faced the problem of where to go, how to live next? By releasing him “cleanly,” the state obliged the retired soldier to “shave his beard” and not engage in begging, and somehow no one cared about anything else...

Retired soldiers had to make their own lives. Some went to the almshouse in old age, some were assigned to be janitors or doormen, some to the city service - depending on age, strength and health...  By the way, It is worth noting that throughout the 19th century, the number of years of military service according to conscription gradually decreased - which means that younger, healthier people retired. Thus, in the second half of the reign of Alexander I, his service in the guard was reduced by three years - to 22 years. But the Blessed One, as Emperor Alexander Pavlovich was officially called, who always looked abroad and was very favorable towards the Poles and Balts, already in 1816 reduced the period of military service in the Kingdom of Poland, which was part of the Russian Empire, to 16 years...

By the way, It is worth noting that throughout the 19th century, the number of years of military service according to conscription gradually decreased - which means that younger, healthier people retired. Thus, in the second half of the reign of Alexander I, his service in the guard was reduced by three years - to 22 years. But the Blessed One, as Emperor Alexander Pavlovich was officially called, who always looked abroad and was very favorable towards the Poles and Balts, already in 1816 reduced the period of military service in the Kingdom of Poland, which was part of the Russian Empire, to 16 years...

In Russia itself, this was achieved only at the end of the reign of his brother, Nicholas I. And then only in several stages - after reductions in 1827, 1829, 1831 and other years - the service life by 1851 gradually reached 15 years.

By the way, there were also “targeted” reductions. IN “The History of the Life Guards of the Izmailovsky Regiment,” for example, states that after the suppression of the rebellion of 1831, “a command was issued that again showed the love, care and gratitude of the monarch to the pacifiers of Poland. This command shortened two years of service for troops who were on the campaign... Those wishing to remain in the service were ordered to receive an additional one and a half salary and, after serving a five-year period from the date of refusal to resign, to turn all this salary into a pension, regardless of the specific state pension.”

« Recruitment set- the old way of recruiting people for our army; began in 1699 and continued until 1874... Recruits were supplied by tax-paying classes. At first, recruitments were random, as needed. They became annual in 1831, with the publication of the recruiting regulations.”

(Small encyclopedic Dictionary. Brockhaus - Efron.)

And since in the conditions of Europe at that time, pacified after the Napoleonic storms, there was no need for extraordinary recruitment, then mostly people 20-25 years old were taken into service. It turned out that by the age of 40 the warrior had already finished his service - it seemed new life It’s still possible to start, but not everyone wanted it, not everyone liked it... So some decided to completely connect their lives with the army, with which they had become close over many years of service.

I would be glad to serve!

Let's take the book “Life Hussars” published last year by Military Publishing House - the history of the Life Guards of His Imperial Majesty the Hussar Regiment - and we will select the following information from there:

“Until 1826... a private who wanted to continue serving after the end of his legal term received a salary increased by a six-month salary...

On August 22, 1826, on the day of the sacred coronation, the sovereign emperor was pleased... to dismiss the lower ranks who had served in the guard for 20 years (23 years in the army)... As for the lower ranks who wished to remain in service even after the appointed time, then... their salary increase was supposed to be increased not only by half salary, but by an additional full salary, that is, for privates who voluntarily remained in the service, their salary was increased two and a half times. But this was not the end of the highest benefits and advantages granted to them.

Those of them who, after refusing to resign, served for another five years, their salary, increased by two and a half times, is supposed to be converted into a pension upon death, and they receive this pension regardless of the funds that are provided to them by the insignia of the Military Order and the Holy Anna."

By the way, as a sign of special distinction, such “contract” warriors received a gold braid patch on their left sleeve, and every five years they were given another patch.

“On July 1, 1829, it was ordered to lower ranks who had served in the rank of non-commissioned officer for 10 years (in the army for 12 years) and, after passing the established exam, refused promotion to officers, to make a payment in the service of two-thirds of the cornet salary and after they had served for five years after Therefore, this salary will be converted into a lifelong pension.”

We already talked about why not all non-commissioned officers wanted to receive chief officer epaulettes and with them the dignity of nobility...

On March 26, 1843, the method of promoting non-commissioned officers to chief officers was changed: all those who passed the exam were divided into two categories based on its results. “Non-commissioned officers who passed the first-class examination in the program received the right to be promoted to army regiments, and for refusing it they enjoyed the following advantages: they had a silver lanyard, a braided sleeve patch, were exempt from corporal punishment and demotion to the rank and file without court... and also to receive two-thirds of the cornet's salary as a pension after service for five years from the date of assignment of this salary.

Non-commissioned officers of the second category, that is, those who passed the weakest examination, were not promoted to officers, but if they wished to remain in the service, they were assigned one-third of the cornet salary, which, after five years of service, was converted into a pension, and at the same time all other advantages were presented non-commissioned officers of the first category, with the exception of only a silver lanyard..."

Unfortunately, A modern military man, wearing our completely impersonal, “non-national” uniform, has no idea how much certain details of ancient uniforms meant. For example, a silver lanyard on a saber or sword was an honorary accessory of an officer’s rank - it was not without reason that after the Battle of Austerlitz on November 20, 1805, when the Novgorod Musketeer Regiment faltered, its officers were deprived of such a distinction. So the lower rank, awarded the silver lanyard, was close to the officers, who now had to address him as “you.”

All of the listed benefits and features of the service of the then “contract soldiers” - and for them there were their own rules for placement and organization of life - not only radically separated them from ordinary soldiers and non-commissioned officers, but also to a certain extent changed the psychology of both themselves and their colleagues in relation to them. These people really had something to lose, and they categorically did not want to return to the original one. And not only because of what they directly gained from the service, but also because of their attitude towards it. People who did not like service did not remain to serve beyond their term and did not refuse the officer rank, which gave the right to retire... But here there was truly selfless love, based on the awareness that a military man is superior to a civilian in all respects. That’s how it was, that’s how we were raised!

It is clear that no one would have dared to call such a “bourbon” a “soldier with stripes,” as the toughest representatives of the non-commissioned, as well as the officer, class were called in those days. This was no longer a soldier, although not an officer at all - he was a representative of precisely that extremely necessary connecting link, which, in the words of one German military theorist, was “the backbone of the army.”

However, it is known that “contract soldiers” in the army of that time performed the duties not only of junior commanders, but also of various kinds of non-combatant specialists, which was also very valuable. An absolutely amazing episode was described by the former cavalry guard Count Ignatiev - I will give his story in abbreviation...

Death of a Stoker

“On one regiment duty, the following happened: in the evening... the non-commissioned officer on duty on a non-combatant team came running and, with excitement in his voice, reported that “Alexander Ivanovich died.”

Everyone, from the private to the regiment commander, called Alexander Ivanovich the old bearded sergeant major who stood for hours next to the orderly at the gate, regularly saluting everyone passing by.

Where did Alexander Ivanovich come to us from? It turned out that still... at the beginning

In the 1870s, the stoves in the regiment smoked incredibly, and no one could cope with them; Once the military district sent a specialist stove maker from the Jewish cantonists, Oshansky, to the regiment. With him, the stoves burned properly, but without him they smoked. Everyone knew this for sure and, bypassing all the rules and laws, they detained Oshansky in the regiment, giving him a uniform, titles, medals and distinctions for long-term “unblemished service”... His sons also served in long-term service, one as a trumpeter, the other as a clerk , the third - a tailor...

I could never have imagined what happened in the next few hours. Luxurious sleighs and carriages drove up to the regimental gates, from which elegant, elegant ladies in furs and respectable gentlemen in top hats emerged; they all made their way to the basement, where the body of Alexander Ivanovich lay. It turned out - and this could not have occurred to any of us - that Sergeant Major Oshansky had been at the head of the St. Petersburg Jewish community for many years. The next morning the body was carried out... In addition to all Jewish St. Petersburg, not only all the available officers of the regiment came here, but also many old cavalry guards, led by all the former commanders of the regiment.”

The given fragment indicates that, firstly, in former times even very respected people entered the “contract service” and, secondly, that in the regiments their “contract soldiers” were truly valued...

However, we always say “in the shelves,” whereas in XIX century in the Russian army there was at least one separate military unit, completely staffed by “contract soldiers”.

Eighty years in service

In issue 19 of the magazine I found the “Bulletin of the Military Clergy” for 1892 completely amazing biography Russian “contract soldier” Vasily Nikolaevich Kochetkov, born in 1785.

In May 1811 - respectively 26 years old - he was taken into military service and assigned to the famous Life Grenadier Regiment, which was soon assigned to the guard and named the Life Guard Grenadier. In 1812, taking part in rearguard battles, this regiment retreated to Mozhaisk, and Kochetkov fought in its ranks at Borodino, and then at Leipzig, taking Paris. Then there was the Turkish War of 1827-1828, where the life grenadiers seemed to justify their presence among the rebel troops in Senate Square December 14, 1825... After that, the Russian guard pretty much beat up the Polish rebels on the Grochowski field and near the town of Ostroleka, and in 1831 the guards grenadiers took part in the capture of Warsaw.

By this time, Kochetkov had just served 20 years, having refused the officer rank - therefore, he was a non-commissioned officer, but he did not “outright” leave, but stayed for extra-long term. Moreover, the old grenadier decided to continue his service not on the St. Petersburg parquets, but in the Caucasian Corps, where he spent five years in battle - and for ten months he was captured by robbers. Vasily Nikolayevich returned from the Caucasus in 1847; he was then already “sixty-odd”; it was time to think about retirement. And he really finished his service - however, only after he visited Hungary in 1849, where the troops of Emperor Nikolai Pavlovich helped the Austrian allies restore order...

Probably, the traces of the grenadier Kochetkov would have been lost, but the events of the Crimean War again called the veteran into service. The old man reached Sevastopol, joined the ranks of those fighting for the city, and even took part in the forays of the besieged garrison. When he returned to St. Petersburg, Emperor Alexander II enlisted the old soldier in the Life Guards Dragoon Regiment, where Kochetkov served for six years, and after that he entered the Palace Grenadier Company - that very special unit where all soldiers served voluntarily... Company served in Winter Palace, and court service clearly did not appeal to the veteran, who soon went to Central Asia, where he fought under the banners of the glorious General Skobelev, winning Samarkand and Khiva... He returned to his company only in 1873 - note, 88 years old. True, he again did not stay here for long, because three years later he volunteered for the active army beyond the Danube and, it’s just scary to think, he fought on Shipka - these are the steepest mountains, completely unimaginable conditions. But the veteran of the Patriotic War of 1812 was able to cope with everything...

Having finished the war, Kochetkov again returned to the Palace Grenadier company, served in it for another 13 years, and then decided to return to his native land. But it didn’t come true... As stated in “Bulletin of the Military Clergy,” “death overtook the poor soldier completely unexpectedly, at a time when he, having received his retirement, was returning to his homeland, rushing to see his relatives and live in peace after a long service.”

Perhaps no one else had a greater combat path than this “contract soldier” grenadier.

Palace Grenadiers

Dvortsov Company The grenadier was formed in 1827 and performed honor guard duty in the Winter Palace. At first, it included guards soldiers who had gone through the entire Patriotic War- first from Neman to Borodino, then from Tarutino to Paris. If the guards, dressed up from the guard regiments, protected the sovereign, then the main task of the palace grenadiers was to maintain order and keep an eye on the cunning court servants - footmen, stokers and other brethren. If in the 20th century they loudly shouted about “civilian control” over the army, then in the 19th century they understood that it would be safer and calmer when disciplined and honest military personnel looked after civilian dodgers...

“Volunteers are persons with educational qualifications who entered voluntarily, without drawing lots, for active military service in the lower ranks. The voluntary service of those who volunteer is based not on a contract, but on the law; it is the same military service, but only with a modification of the nature of its implementation.”

(Military Encyclopedia. 1912).

At first, old-timers were selected for the company, and later they began to recruit those who had fully served their term, that is, “contract soldiers.” At the behest of Emperor Nicholas I, he immediately determined that the salary was very good: non-commissioned officers equal in rank to army warrant officers - 700 rubles per year, grenadiers of the first article - 350, grenadiers of the second article - 300. A non-commissioned officer of the palace grenadiers was actually an officer , so he received an officer’s salary. Such obscenity, that even a “contract” soldier of even the most “elite” unit received a salary greater than an officer’s, has never happened in the Russian army. By the way, in the company guarding the Winter Palace, not only were “contract” soldiers serving, but all its officers were promoted from ordinary soldiers, they began their service as the same recruits as their subordinates!

It can be understood that Emperor Nicholas I, who founded this company, had special confidence in it, which the palace grenadiers fully justified. Suffice it to recall the fire in the Winter Palace on December 17, 1837, when they, together with the Preobrazhensk guards, carried out portraits of generals from Military gallery 1812 and the most valuable palace property.

After all, they were always guided by what is considered the most expensive here, what requires special attention... By the way, here it is worth remembering how Emperor Nikolai Pavlovich appeared in the middle of the burning hall and, seeing that the grenadiers, straining themselves, were dragging a huge Venetian mirror, told them: “No need, guys, leave it! Save yourself!” - “Your Majesty! – one of the soldiers objected. “It’s impossible, it costs so much money!” The king calmly broke the mirror with a candelabra: “Now leave it!”

Two of the grenadiers - non-commissioned officer Alexander Ivanov and Savely Pavlukhin - died then in a burning building... Real army service is never easy, it is always fraught with some potential danger. In previous times, they tried to compensate for this “risk factor” at least financially...

...That's basically it and everything that I would like to tell about the history of “contract service” in Russia. As you can see, it was not something far-fetched or artificial, and, provided its organization was comprehensively thought out, it brought considerable benefits to the army and to Russia.

However, it would be worth recalling that never – even at the very beginning of its history – our regular army was purely “contract”. “Contract soldiers”, no matter how they were called, were an elite part of the “lower ranks”, they were a reliable link between officers, command staff and the rank and file, non-commissioned officers, the “backbone” of that very Russian army that fought bravely at Poltava and Borodino, defended Sevastopol, crossed the Balkans and, thanks to the mediocrity of the highest state leadership, disappeared undefeated on the fields of the First World War.

In the pictures: Unknown artist. Palace Grenadier.

V. SHIRKOV. Extra-conscript private of the Yamburg Uhlan Regiment. 1845.

As you know, the great sovereign Peter Alekseevich made many changes in our country. Historians can spend hours listing the innovations of the reformer tsar; they will also note that under Peter 1 the army was formed on the basis of a set of recruits.

Peter spent a very serious military reform, which strengthened the Russian Empire and contributed to the fact that our country and its army were stronger than the army of the Swedish conqueror Charlemagne, which held all of Europe at that time in fear.

But first things first.

Why was there a need to carry out army reform?

When Pyotr Alekseevich was crowned king together with his brother Ivan Alekseevich, the army in Russia was as follows:

- From regular units - Streltsy regiments, Cossack formations and foreign mercenaries.

- Of the temporary formations in the event of a military threat - local troops, which were collected from peasants and artisans by large feudal lords.

During the turbulent 17th century, our country experienced many military upheavals; in the end, it was saved from the Time of Troubles not only by the military courage of regular units, but also by the forces

Were there any attempts to create a regular army before Peter the Great?

Peter's father, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, also thought about a regular army, in which there would be conscription. However, his sudden death did not allow him to carry out all his military plans, although the king tried to partially bring them to life.

His eldest son and heir was seriously ill, governing the state was difficult for him, and he died soon after the death of his father.

The sister of Peter and John - the heirs to the throne - Princess Sofya Alekseevna, who actually usurped the power of her young brothers, relied on the archers. It was through the teaching of people loyal to Sophia that she actually received royal power.

However, the archers demanded privileges from her, and Sophia did not skimp on them. Her faithful assistants thought little about their service, which is why the army of the Russian state at that time was relatively weak compared to the armies of other European states.

What did Peter do?

As you know, Peter the Great’s path to power was very difficult; his sister interfered with him, wanting him dead. As a result, the young king managed to win the battle with Sophia, brutally suppressing her supporters of the Streltsy.

The young sovereign dreamed of military victories, but where could they get them in a country that actually did not have a regular army?

Peter, with his characteristic ardor, zealously got down to business.

So, under Peter 1, the army was formed on the basis of completely new principles.

The tsar began by organizing his two “amusing regiments” - Preobrazhensky and Semyonovsky - according to the European model. They were commanded by foreign mercenaries. The shelves showed themselves with the best side during the Battle of Azov, so already in 1698 the old troops were completely disbanded.

In return, the king ordered the recruitment of new military personnel. From now on, conscription was imposed on every populated area of the country. It was necessary to provide a certain number of young, physically strong men for their service to the Tsar and the Fatherland.

Military transformations

As a result, they managed to recruit about 40,000 people, who were divided into 25 infantry regiments and 2 cavalry regiments. The commanders were mostly foreign officers. The soldiers were trained very strictly and according to the European model.

Peter was impatient to go with his new army to battle. However, his first military campaign ended in defeat near Narva.

But the king did not give up. Under Peter 1, the army was formed on the basis of recruitment, and this became a condition for its success. In 1705, the tsar issued an order, according to which such recruitment was to become regular.

What was this service like?

The service for the soldiers was long and hard. The service life was 25 years. Moreover, for showing courage in battle, a simple soldier could rise to the rank of officer. Peter generally did not like lazy scions from rich families, so if he noticed that some dressed-up young nobleman was evading his official duties, he did not spare him.

Particular importance was given to the military training of the nobility, who were required to perform military service for 25 years. In return for this service, the nobles received land plots from the state with the peasants.

What has changed?

Despite the fact that the population reacted negatively to the heavy conscription duty, trying in every possible way to avoid it (young people were sent to monasteries, assigned to other classes, etc.), the army of Peter I grew. At the moment when the Swedish king Charles decided to defeat our country, Peter already had 32 infantry regiments, 2 regiments of guards and 4 regiments of grenadiers. In addition, there were 32 special dragoon regiments. It was about 60 thousand well-trained soldiers under the command of experienced officers.

This army was enormous power, which ensured the Russian sovereign his military victories in the near future.

Results of Peter's reform

As a result, by his death in 1725, the king had created an entire military machine, which was distinguished by its power and efficiency in military affairs. Of course, the creation of the army by Peter 1 is a huge merit of the sovereign. In addition, the tsar created special economic institutions that provided his army with the possibility of subsistence, created regulations for service, conscription, etc.

Representatives of all classes were required to serve in this army, including the clergy (priests performed their direct functions in it).

Thus, we can say with confidence that under Peter 1 the army was formed on the basis of universal recruitment. It was a strict and strong military system, a well-coordinated social mechanism that ensured the fulfillment of its main task - protecting the country from external threats in that turbulent time.

Seeing such an army, the Western powers simply lost the desire to fight with Russia, which ensured our country’s relatively successful development in subsequent centuries. In general, the army created by Peter, in its main features, existed until 1917, when it was destroyed under the onslaught of well-known revolutionary events in our country.

How was conscription carried out into the army of Imperial Russia at the beginning of the 20th century. Who was subject to it? Those who had conscription benefits, monetary rewards for military personnel. Collection of statistics.

"Of all the subjects of the Russian Empire who had reached conscription age (20 years), about 1/3 - 450,000 out of 1,300,000 people - were called up for active military service by lot. The rest were enlisted in the militia, where they were trained at short training camps.

Call once a year - from September 15 or October 1 to November 1 or 15 - depending on the timing of the harvest.

Duration of service in the ground forces: 3 years in infantry and artillery (except cavalry); 4 years in other branches of the military.

After this, they were enlisted in the reserves, which were called up only in case of war. The reserve period is 13-15 years.

In the navy, conscript service is 5 years and 5 years in reserve.

The following were not subject to conscription for military service:

Residents of remote places: Kamchatka, Sakhalin, some areas of the Yakut region, Yenisei province, Tomsk, Tobolsk provinces, as well as Finland. Foreigners of Siberia (except for Koreans and Bukhtarminians), Astrakhan, Arkhangelsk provinces, Steppe Territory, Transcaspian region and the population of Turkestan. Some foreigners of the Caucasus region and Stavropol province (Kurds, Abkhazians, Kalmyks, Nogais, etc.) pay a cash tax instead of military service; Finland deducts 12 million marks from the treasury annually. Persons of Jewish nationality are not allowed into the fleet.

Benefits based on marital status:

Not subject to conscription:

1. The only son in family.

2. The only son capable of working with an incapacitated father or widowed mother.

3. The only brother for orphans under 16 years of age.

4. The only grandchild with an incapacitated grandmother and grandfather without adult sons.

5. Illegitimate son with his mother (in his care).

6. Lonely widower with children.

Subject to conscription in the event of a shortage of suitable conscripts:

1. The only son capable of working, with an elderly father (50 years old).

2. Following a brother who died or went missing in service.

3. Following his brother, still serving in the army.

Deferments and benefits for education:

Receive a deferment from conscription:

up to 30 years of age, government scholarship holders preparing to take up scientific and educational positions, after which they are completely released;

up to 28 years of age, students of higher educational institutions with a 5-year course;

up to 27 years of age in higher education institutions with a 4-year course;

up to 24 years of age, students of secondary educational institutions;

students of all schools, upon request and agreement of ministers;

for 5 years - candidates for preaching of Evangelical Lutherans.

(In wartime, persons who have the above benefits are taken into service until the end of the course according to the Highest permission).

Reduction of active service periods:

Persons with higher, secondary (1st rank) and lower (2nd rank) education serve in the military for 3 years;

Persons who have passed the reserve warrant officer exam serve for 2 years;

doctors and pharmacists serve in the ranks for 4 months, and then serve in their specialty for 1 year 8 months

in the navy, persons with an 11th grade education (lower educational institutions) serve for 2 years and are in the reserve for 7 years.

Benefits based on professional affiliation

The following are exempt from military service:

- Christian and Muslim clergy (muezzins are at least 22 years old).

- Scientists (academicians, adjuncts, professors, lecturers with assistants, lecturers of oriental languages, associate professors and private assistant professors).

- Artists of the Academy of Arts sent abroad for improvement.

- Some academic and educational officials.

Privileges:

- Teachers and academic and educational officials serve for 2 years, and under the temporary 5-year position from December 1, 1912 - 1 year.

- Paramedics who have graduated from special naval and military schools serve for 1.5 years.

- Graduates of the schools for soldiers' children of the Guard troops serve for 5 years, starting from the age of 18-20.

- Technicians and pyrotechnicians of the artillery department serve for 4 years after graduation.

- Civilian seamen are given a deferment until the end of the contract (no more than a year).

- Persons with higher and secondary education are accepted into service voluntarily from the age of 17. Service life - 2 years.

Those who pass the exam for the rank of reserve officer serve for 1.5 years.

Those volunteering for the navy - only with higher education— service life 2 years.

Persons who do not have the above education can voluntarily enter the service without drawing lots, the so-called. hunters. They serve on a general basis.

Cossack conscription

(Taked as a sample Don Army, other Cossack troops serve in accordance with their traditions).

All men are required to serve without ransom or replacement on their own horses with their own equipment.

The entire army provides servicemen and militias. Servicemen are divided into 3 categories: 1 preparatory (20-21 years old) undergoes military training. II combatant (21-33 years old) is directly serving. III reserve (33-38 years old) deploys troops for war and replenishes losses. During the war, everyone serves without regard to rank.

Militia - all those capable of service, but not included in the service, form special units.

Cossacks have benefits: according to marital status (1 employee in the family, 2 or more family members are already serving); by property (fire victims who became impoverished for no reason of their own); by education (depending on education, they serve from 1 to 3 years in service).

2. Composition of the ground army

All ground troops are divided into regular, Cossack, police and militia. — the police are formed from volunteers (mostly foreigners) as needed in peacetime and wartime.

By branch, the troops consist of:

- infantry

- cavalry

- artillery

- technical troops (engineering, railway, aeronautical);

- in addition - auxiliary units (border guards, convoy units, disciplinary units, etc.).

- b) cavalry is divided into guards and army.

- 4 - cuirassiers

- 1 - dragoon

- 1 - horse grenadier

- 2 - Uhlan

- 2 - hussars

The Army Cavalry Division consists of; from 1 dragoon, 1 uhlan, 1 hussar, 1 Cossack regiment.

Guards cuirassier regiments consist of 4 squadrons, the remaining army and guards regiments consist of 6 squadrons, each of which has 4 platoons. Composition of the cavalry regiment: 1000 lower ranks with 900 horses, not counting officers. In addition to the Cossack regiments included in the regular divisions, special Cossack divisions and brigades are also formed.

3. Fleet composition

All ships are divided into 15 classes:

1. Battleships.

2. Armored cruisers.

3. Cruisers.

4. Destroyers.

5. Destroyers.

6. Minor boats.

7. Barriers.

8. Submarines.

9. Gunboats.

10. River gunboats.

11. Transports.

12. Messenger ships.

14. Training ships.

15. Port ships.

The infantry is divided into guards, grenadier and army. The division consists of 2 brigades, in the brigade there are 2 regiments. The infantry regiment consists of 4 battalions (some of 2). The battalion consists of 4 companies.

In addition, the regiments have machine gun teams, communications teams, mounted orderlies and scouts.

The total strength of the regiment in peacetime is about 1900 people.

Guards regular regiments - 10

In addition, 3 Guards Cossack regiments.

Source: Russian Suvorin calendar for 1914. St. Petersburg, 1914. P.331.

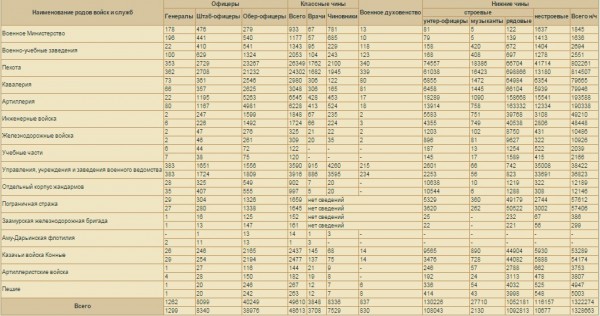

Composition of the Russian Army as of April 1912 by branch of service and departmental services (by staff/lists)

Source:Military statistical yearbook of the army for 1912. St. Petersburg, 1914. P. 26, 27, 54, 55.

Composition of army officers by education, marital status, class, age, as of April 1912

Source: Military Statistical Yearbook of the Army for 1912. St. Petersburg, 1914. P.228-230.

Composition of the lower ranks of the army by education, marital status, class, nationality and occupation before entering military service